Behind Scouting's new Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Merit Badge

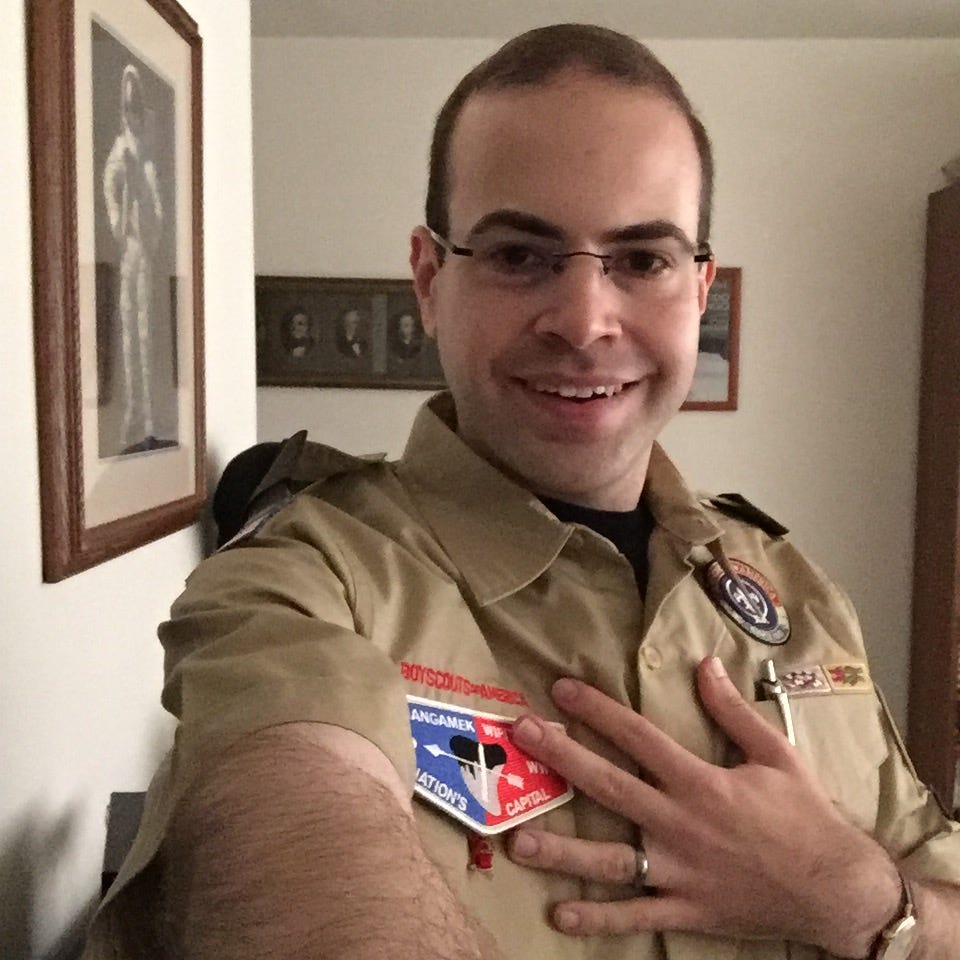

Sam Aronson is among the leaders of Scouting's efforts to become a more welcoming place for historically marginalized groups. He shares what that experience has been like so far.

Sam Aronson doesn’t owe anything to the Boy Scouts of America.

After he earned his Eagle Scout rank, he left the organization because he was not allowed to be an openly gay adult volunteer. That very well could have been where his Scouting journey ended. And no one could blame him for that.

But the moment the ban on gay members fell in 2015, Sam got right back into Scouting, joining a local troop in Washington, D.C. as an assistant scoutmaster.

And that’s not where Sam’s contributions to Scouting end. He’s now one of the authors of a new Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Merit Badge, and leading efforts to make the BSA a more welcoming place for historically marginalized groups. What follows is a Q&A I did with Sam about all of that and more.

How did you first get involved in Scouting?

I imagine like a lot of other people in the organization, it wasn't so much as I “got involved,” as one Wednesday night my parents put me in the car, in first grade, and drove me to the local Catholic church. And there I was in a bright orange T-shirt that said, Tiger Cubs BSA on it. I was a Scout.

What was it about Scouting that made you stay involved?

Definitely the number one thing was friendships. Some of the closest friends I had as a young person were friends I had in my Boy Scout troop. The troop itself was not particularly big, we had 20-25 guys in it. Several of them were really close friends of mine, their families were close with my family.

The second thing was, I just found myself feeling really good in Scouting spaces, in a way I didn't or couldn't in other spaces. The town that I grew up in is in northern New Jersey, but it sort of fancied itself or acted like the town from “Varsity Blues” in Texas, where they thought of football as a religion, and everyone in my town was expected to do lots of sports. And I felt like a real outsider there. I was the kid who was always picked last in gym, and picked begrudgingly.

But that never was the case in my troop. I felt like even though I wasn't great at knots and lashings, I was better at first aid, it didn't matter that you couldn't be perfect in every space in Scouting. And I felt like it was a space that I could excel in, even though I wasn't the most physically fit or the best pioneer. And I'm convinced to this day that's what makes Scouting really good.

Also, I was queer. And while I wasn't out in high school, I certainly knew that. And yet somehow I felt accepted. Not that I was especially bullied in high school. But I definitely wasn't in Scouting, and again I felt pretty welcomed and accepted. And I felt like I was a place I belonged.

One thing that really resonates me, that I've heard from many Scouts, is this idea that as a queer kid, or as someone who didn't fit the traditional box, Scouting was an expansive space for you to fit in. Which I think is really ironic given the organization's stance on gay people, and also just the idea that it's a place for "traditional manhood." As a youth, did you every feel that tension?

As a young person, I never felt that incongruence, that Scouting was this hyper-masculine place. I do think I felt that in gym, in high school gym class, I felt like I was unwelcome here. But Scouting, for that in some ways I also want to credit the adults, that each local unit really exists unto itself. And that regardless of your district and council and region, whatever culture they have there, it's really about the leadership and the other Scouts who are there. And the leadership that I had in my troop, and the other Scouts in my troop, certainly was a product of that town. People played sports and we'd build our camping, hiking weekend schedule around the sports stuff. But I think the emphasis was not that your place in the troop or your place in the unit had anything to do with your abilities, but it had a lot to do with your interests and beliefs and values.

You're now active as an adult volunteer. What has that experience been like?

It's hard for me to talk about this without talking about my separation with Scouting. I joined as early as you possibly could, and I stuck through high school, and then even when I was in college I was an assistant scoutmaster of the troop I was part of, and I worked on camp staff and was involved in my Order of the Arrow lodge through the time I was 21.

At that time, the scout executive from my local council … sat me down and said, his exact words were, "This is going to be a one-way conversation, Sam. Everyone here knows [your] sexual preference and you know that that's not permissible, and so you have to make a choice now. If you don't renew your membership, we don't investigate people who are non-members. But if you want to stay involved, you'd be investigated, you probably know how that's going to end up." And so I said to him, "Thank you for telling me that, I will not renew my dues this year." And that's what I did at 21, I ended that. But while my involvement with Scouting ended formally, the relationships and friendships [continued.] When I got married, many of the people who danced at my wedding were people I met in my lodge.

I'm glossing over the pain of that experience, I was hurt by it. This was the one place where I really felt at home, certainly when I was in high school, telling me that I wasn't welcome. … I actually had a very close mentor, an older man in my lodge, who was clearly gay, and he made a different choice. He made a choice to lead a closeted life. And he let me know that was an option, and for me it wasn't. It just was not something I was willing to do. So I always jokingly told friends, I'm happy to go back hiking and camping and get dirty and things like that the moment I can do it without lying.

And then the summer of 2015, the policy around queer adult leaders changed, and I did have literally three friends who called me within a week and said, "Alright Sam, the policy has changed. It's time to put your boots back on." And at this point I'd spent a decade becoming really comfortable with a good concierge at hotels, but I made a promise.

So within 90 days of the policy being changed, I found a local Troop where I now live in D.C., and I talked to the scoutmaster and troop committee chairman, and let them know about my record in Scouting, my experience, and I said, “And I'm gay, and I want you to know that. I'm not going to make a big deal out of it, but I need you to know that, that's why I took a break, but I'm not going to hide any part of my life." And they said, "We are excited to have an Eagle Scout, a Vigil Honor member of the OA." None of the adult leaders are, so they were excited to have me join the troop. My first return to Scouting was and remains being an assistant scoutmaster of a local troop here in D.C. And it's been a lot of fun, it's been a good experience and I'm grateful for that.

Our paths crossed when you started doing diversity trainings at Scouting events around the country. And then you also became involved in writing the soon-to-be-released Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Merit Badge. What were some of the priorities going into that, and how do you think it has turned out?

This past summer after the murder of George Floyd and the protests that ensued because of his murder and the murder of Breonna Taylor, the BSA like many organizations released a statement committing themselves to doing more diversity work. And I want to give credit to them, not just doing lip service or being performative, they specifically wanted to put tangibles behind it. And they committed to creating an Eagle-required merit badge on diversity.

The priority behind it, the charter that was given to our committee of authors for the badge, included ... that we had to center the under-represented identities in Scouting, particularly supporting race, Scouts who are LGBTQ, women, people of different ability levels, under-represented faith traditions as well. We wanted to make sure that this was a badge that really would get it right. That we we weren't going to limit it, we weren't going to not talk about things.

We would specifically talk about what it means in the context of Scouting to be an “upstander,” so preventing and countering bullying. And then how to go about creating inclusive and welcoming spaces at local Scouting units. And I'm quite convinced the requirements and the supporting material will achieve that.

How do you “get it right?” How do you approach that as one of the authors of the badge?

No one was shy at the national office of saying that there are a lot more eyes on this than there would be on, I won't pick on any other badge but ...

Basket Weaving?

Exactly, there's not a lot of eyes on Basket Weaving. And it was very clear there were going to be a lot of eyes on this. We had that, but also we were told we were going to get a lot of support, too. That members of the national committee and national office were going to — provided we could back up everything we had to say and wrote with appropriate literature and that it was developmentally appropriate for young people — they were going to do that.

The merit badge program is not designed to be a comprehensive training on anything, but rather it's meant to be an introduction to a specific area. So in some ways I found that a little liberating, because I was worried, how can you get it right, get diversity work right in one badge? So it helped us to focus.

There was an emphasis early on, the language that was used was "neutrality." Like, we have to be "neutral." And that's something that a lot of us on the committee quickly rejected. We said, "We're not going to be neutral in the face of bigotry or oppression or homophobia." It's actually written into the note to the counselor, the concept that Scouts understand that neutrality does not help the marginalized, does not help the vulnerable, neutrality only ever helps the oppressor. So Scouts are expected to be upstanders. It's incumbent open them. To live the Scout Oath and Law requires you to, safely and respectfully when you can, intervene when you encounter bigotry or hate or discrimination. That's what it means to be a Scout.

There were a lot of people who said, "We have the Scout and Oath and Law, why do we need anything else? We don't need anything else, this is unnecessary, you're introducing politics." And when we talked about neutrality, we said there will be no neutrality when it comes to animus, bigotry and hate. But this is something that anyone who's honest, who cares about Scouting, can look at the requirements, and you will never know who anyone on our committee voted for, nor will you be able to say there's anything incongruent between the values of Scouting and what we wrote and what a young person is expected to learn there.

We also can't ignore the fact that Scouting is not apolitical to begin with. At least not in my experience. Each troop is such an individual group of people, that it will inherently have political views, whether they're implicit or explicit.

But I also know as part of this work you've been doing listening sessions with various groups within Scouting. What were some of the biggest takeaways from that?

We had nine listening sessions over the course of a couple months. Each of the identities that we wanted to elevate in those listening sessions were identities of people who have been traditionally under-represented or explicitly excluded from Scouting over the years. We started with Black Scouts; Latinx and Hispanic Scouts; Scouts with disabilities; women; LGBTQ Scouts; Scouts from non-dominant faith traditions; Scouts who were Asian and Pacific Islanders; Scouts who are indigenous; and youth, people under 40.

It was incredibly moving and humbling to hear from some people I had already met, many people I never knew. All of whom shared a deep belief in Scouting. Even people who, like myself, were banned for some time. There were Scouts who were banned for decades, Scouts who earned an Eagle Scout and have since transitioned and are now women, who talked about how much Scouting meant to them and still does. And it so moved me to hear from so many people. People of color who in Scouting spaces experienced real bigotry and hatred, who still love and care about our program. So that's something that reminded me of what makes this so special, and why I love being a part of it — was even though Scouting has done us wrong, it still has managed to weave itself both into the fabric of America, but also weave itself into the souls of millions of people in Scouts, even when it doesn't feel so good.

If you could wave your magic wand today and change one thing about Scouting, what would it be?

That's so tough. Right now, we are in such a horrific place, because of coronavirus just devastating our finances, the membership being devastated by the coronavirus. The lawsuits, the 100,000 [sexual abuse] plaintiffs. The bankruptcy lawyers have said there's a chance this will be the most complex bankruptcy in history. There's never been more plaintiffs. This year in particular has just created such a confluence nightmare with those things, that I feel like I would be irresponsible as a Scout to not say: People have been harmed by Scouting. Whether it's because of sexual abuse or because of discrimination. That would be the thing that, you must honor the victims and repair that.

But if you're asking me, what I would change moving forward ... What I would change is allowing the wider world to understand that our organization is imperfect and is complicated, but no different than the way the United States of America was founded by and for straight, white, wealthy, Christian men, our organization was founded by and for straight, white, wealthy, Christian men. And despite our history of exclusion, we're a place that you and I are living proof can be a welcoming place that allows young people who otherwise feel at home nowhere, it allows them to have that home. And I don't want that to go away. I want that to persist. And it will only persist if we can keep growing our membership, and it's only going to happen if the perception changes, and I'm convinced that we have to lean into this work and talk about it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.