Living History Project: Scouting as the safer place

When schools and families failed them, these LGBTQ+ scouts found solace in Scouting.

In the decade since the Boy Scouts of America has started admitting openly queer members, some scouts have found it to be a uniquely affirming place, especially when their families or communities were not.

Why it matters: This is one of the takeaways in my conversations for the ArrowPride Living History Project. As some of you might remember, I spent my week at the National Order of the Arrow conference in 2022 talking to LGBTQ+ scouters and capturing their stories.

- I’ve finally finished sorting through the material, and I’ll be sharing some of the highlights here in my newsletter, organized around the major themes.

First up: Scouting’s power to be an affirming space for scouts that have no other.

- This is not universally the case—plenty of my interviewees also spoke about homophobic troops or scout leaders (we’ll get to that in a future newsletter). But just as many spoke about scout units, camps and events that were uniquely inclusive.

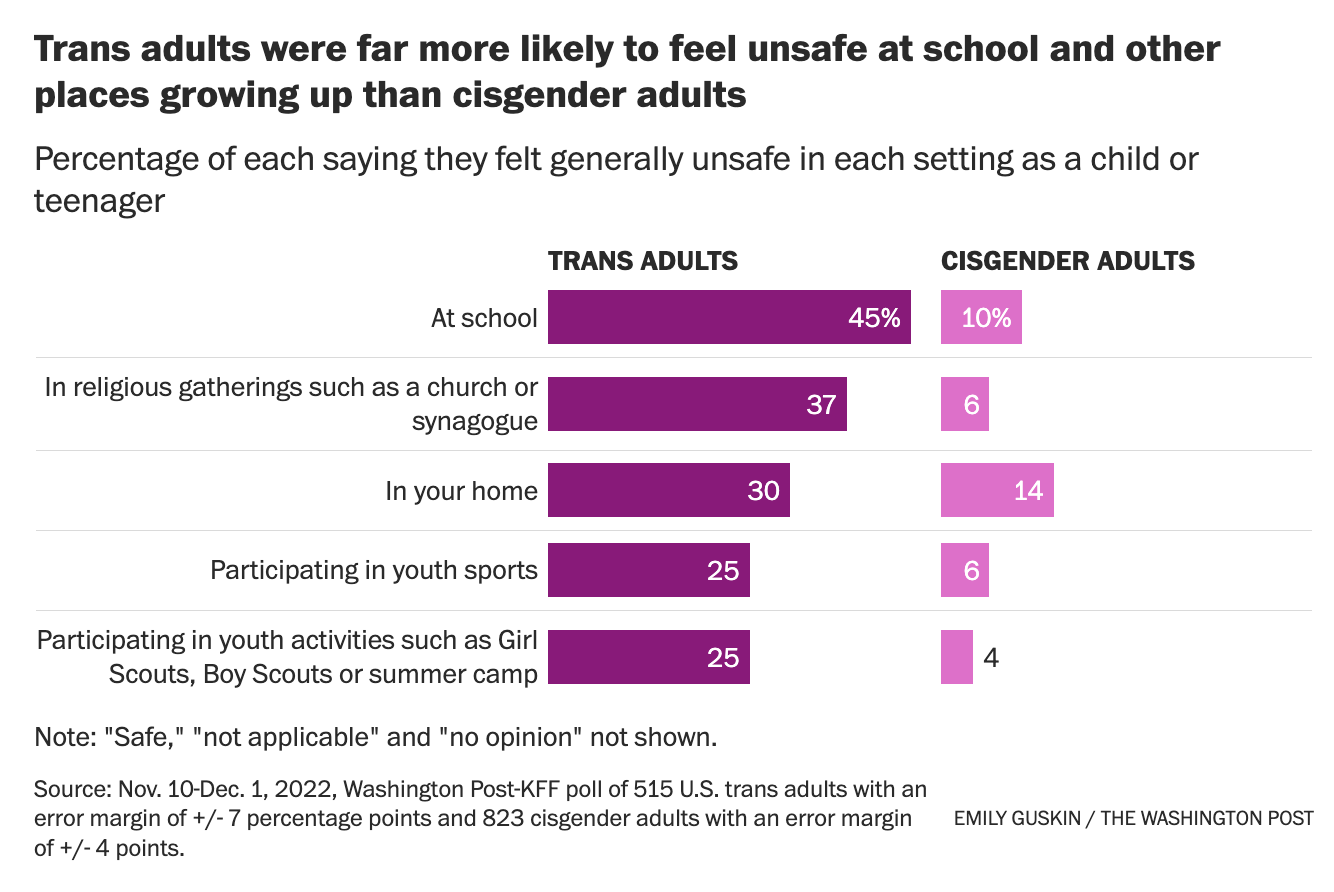

- It’s not just anecdotal: A Washington Post poll from 2022 ranked Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts programs as the environment where transgender kids felt safest—safer than school, church or home.

Of course, the fact that 25 percent of trans kids still felt unsafe in Scouting environments is totally unacceptable. But I think it’s nonetheless striking that this is the lowest percentage of all options on the survey.

And my conversations with queer scouters in the Living History studio backed that up.

‘Scouting literally saved my life’

Boy Scout summer camp was the first place that Thomas Driscoll ever came out to anyone.

“It was the first place [and] the only place for three or four years. And it really helped me throughout middle school,” Driscoll told me. “Scouting literally saved my life because of that.”

He grew up in a small town, where there were hardly any openly LGBTQ+ people. On top of that, his sexuality as a gay man was an unspoken topic at home.

The day after Driscoll graduated high school, he went back to the one place he felt safe: Scout camp, where he was working on staff by that point. After college, he settled in Atlanta, and went to work managing warehouses for Walmart.

But even at a large corporation that publicly touts LGBTQ+ acceptance, Driscoll faced anti-gay attitudes from his coworkers. “When I started there, I was very closeted. A lot of openly homophobic comments were made,” Driscoll said. (He’s since moved on to a job at Harbor Freight, where he says his teams are “fully accepting.”)

To this day, Scouting is one of the places where he feels most affirmed in his identity—which is exactly what keeps him coming back. “I definitely feel it's part of the reason that I still come to NOACs,” Driscoll said.

A queer oasis at scout camp

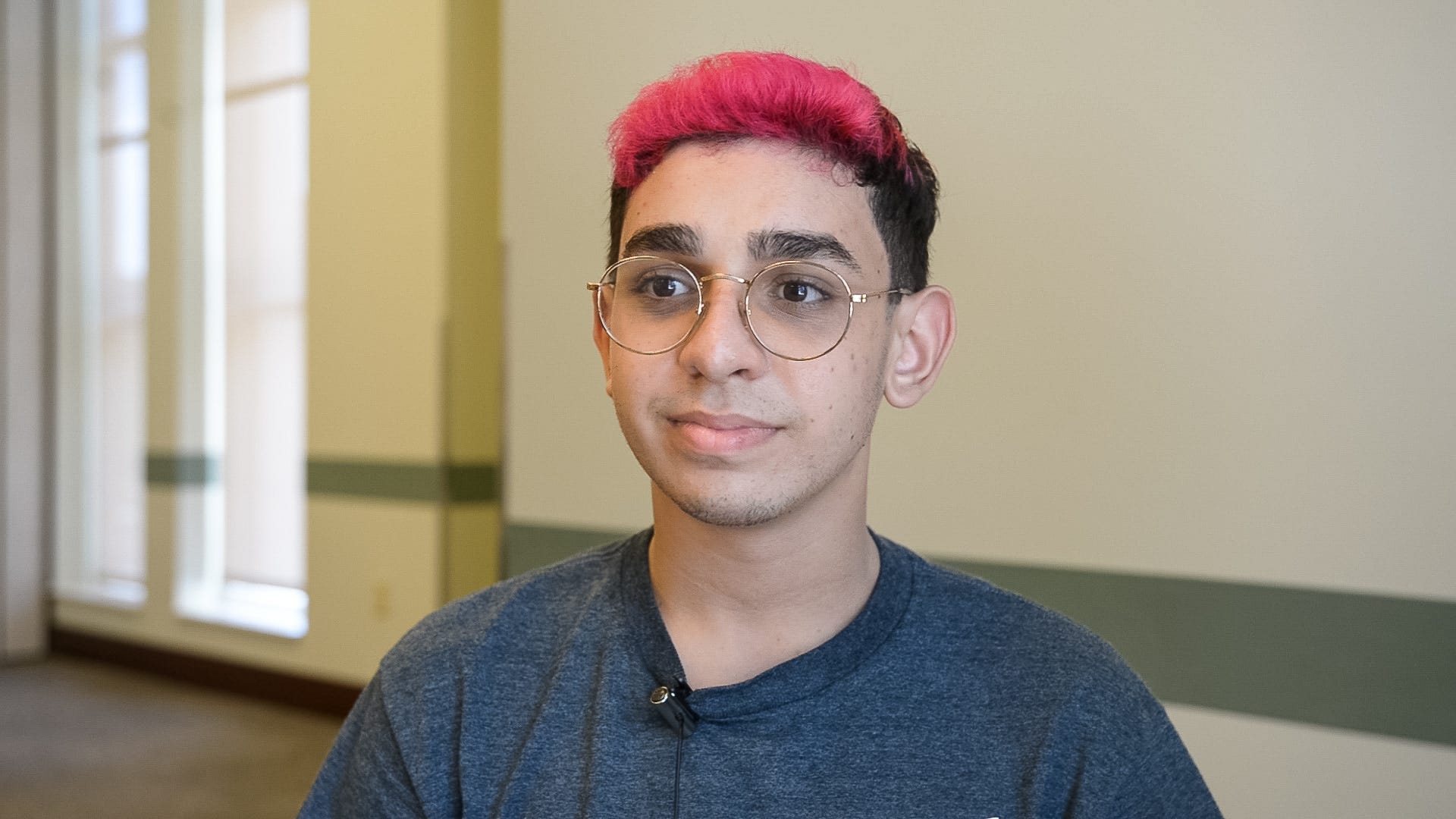

It took Robert Rosado a long time to accept himself as gay.

“I recently just got out of the closet … Before that, it was kind of challenging, because I didn't want to give fruity vibes,” he told me. He didn’t want someone to look at the way he spoke or acted and assume his sexuality. “I was trying to hide it.”

But long before he officially came out, there was one place where felt he didn’t need to hide: Scout camp.

“For me, it's like a Disney park. I can express myself however I want. I can talk however I want,” he said. “It's a happy place for me, a moment where I get apart from my family, and spend some time with other queer scouts.”

That was an essential and rare space growing up in Puerto Rico, where Rosado said his community was “a little conservative,” and LGBTQ+ people were “not that present.”

At scout camp, he was among his peers, even if most of them were in the closet too. But Rosado reports that most of them have since come out alongside him.

“I managed to find my people, I managed to find my group. And that helped me a lot, honestly,” he said. “That reassures my identity, my sexuality, my everything.”

Coming out, a long time coming

When Eric Stupar was growing up in the 1980s, in southeastern Virginia, coming out as a gay person was unthinkable.

“This was the … middle of the AIDS crisis. There was no such thing as a GSA. It was not safe to come out at that point,” Stupar told me.

His scout troop was no exception. Nor was the military, where he enlisted during the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” era. “It forced me to hide part of myself, from when I was a teenager, all the way until I finally came out when I was 44,” he said.

He did so a couple of years ago with a Facebook post, which drew mostly supportive comments from friends and family.

But what really surprised him was that the fellow scouters on his Wood Badge staff were also 100 percent supportive. “It was a very liberating experience that I could then truly be be myself with people,” Stupar said. His council in Baltimore is a mix of progressive folks from the city and more conservative members from the outlying counties. “I was surprised [that] even people who I know their politics are very to the right, were very supportive,” he explained.

It’s a level of acceptance that Stupar never had as a youth in Scouting, but one that he’s now committed to providing for the youth in his charge. “As long as you do it within the confines of scouting, 100 percent, just be yourself.”