Living History Project: The power of an accepting adult

For LGBTQ scouts, even a single affirming adult can make an enormous difference in their life.

Adult scout leaders can be a lifeline for LGBTQ scouts who are facing homophobia from their peers, families or communities.

- This is my third takeaway from the ArrowPride Living History Project. (You can read the first one and second one here.)

Why it matters: The many LGBTQ scouts who find themselves drawn to the program often lack role models at home or in school. An accepting adult, whether LGBTQ or simply an ally, can make a big impact on their mental health.

- Case in point: Only 43% of LGBTQ youth report that their home is an affirming space, meaning scoutmasters have a huge opportunity to fill the gap.

In my conversations for this project, I consistently heard scouters tell me how important it was to have—or be—an accepting adult. Here are some of the highlights.

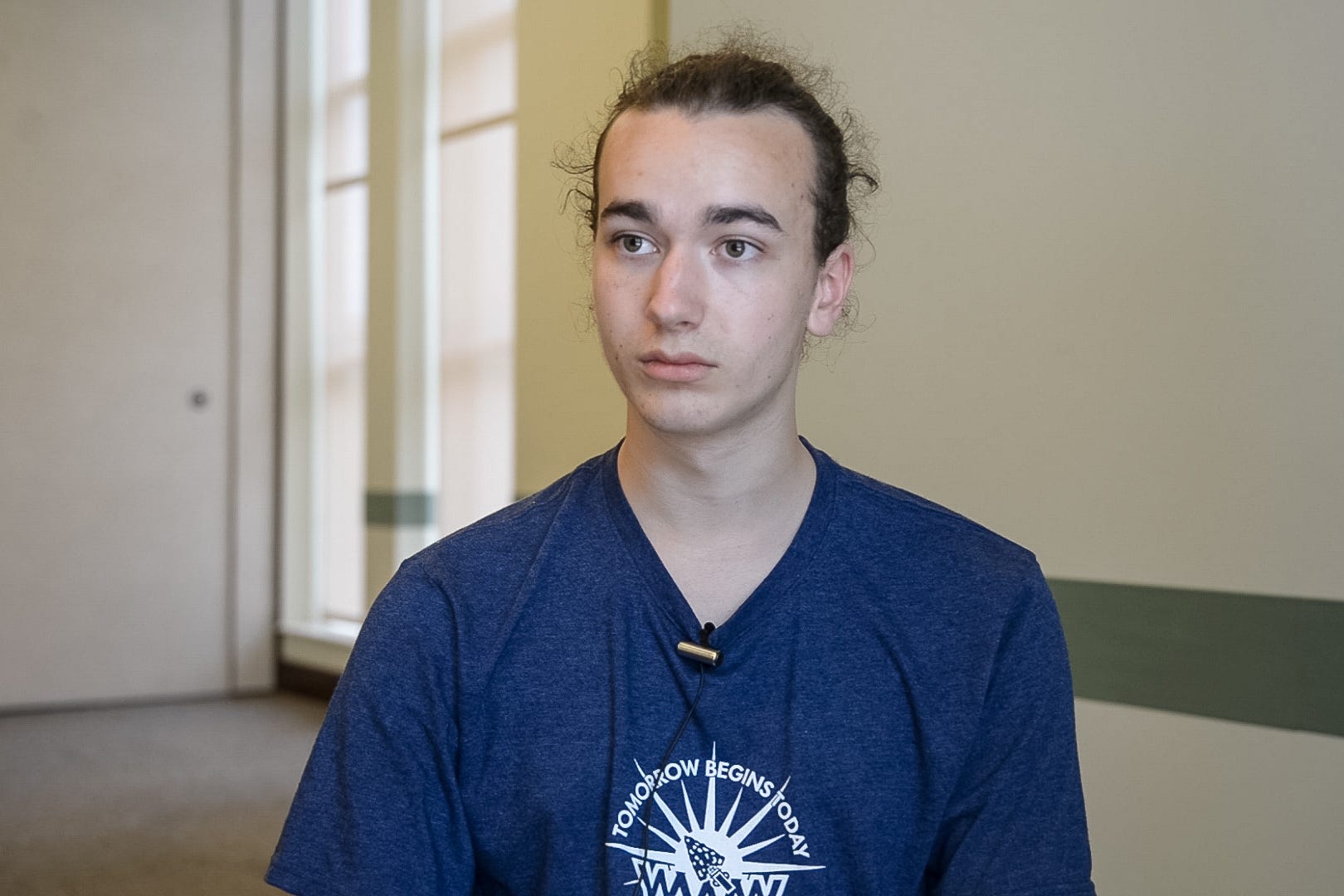

‘I saw people who would step up for me’

As someone who was homeschooled, Luka Shaefers turned to Scouting for almost of all of his social interactions. “It's been my whole world,” he told me.

That world, however, has not always been kind to him. “I've seen a lot of unkindness in Scouting as a gay youth and now man. I've seen a lot of grace as well,” he said. While he once heard some of his fellow scouts say “they wanted to kill gays,” those scarier experiences also showed him who would stand up for him.

At a recent NYLT program, Shaefers turned to the camp medic during a moment of emotional overwhelm. “She set me up with a Gatorade and she listened to me speak,” he recalls. “She was really kind, and she was up to bat for me, she cared.”

Those types of adult leaders epitomize the type that Shaefers believes are essential for LGBTQ youth in the program.

“You ask how I've succeeded in Scouts, in spite of these difficulties. And the truth of the matter is, just as I've seen a lot of a lot of difficulty, that was also the time when I saw a lot of people become my hero,” Shaefers said.

It informs his vision for the future, too: “I want to see adult leaders who feel comfortable being out and being gay or lesbian or trans or anything. So that their charges, their scouts can look to them and say, ‘Well, you know, Mr. Scoutmaster is gay, I can be gay, and I can be safe here, and he'll be up to bat for me if there's an issue. He'll care”

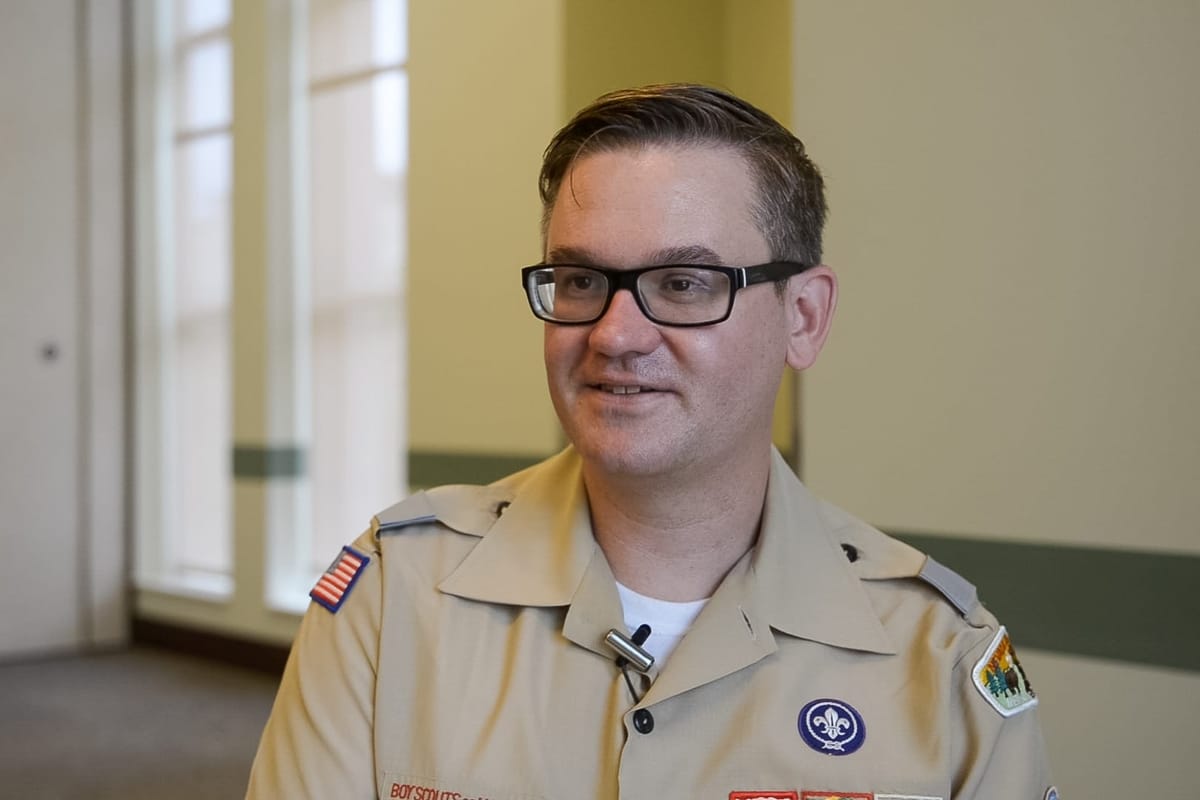

‘Every every kid deserves a Scouting experience’

Ross Armstrong succeeded at a level that few in Scouting ever reach: He checked off every achievement as a youth, and went on to become the Western Region chief of the OA in 2005.

But despite all the accolades, Armstrong was burying a truth about himself: He was gay. After really coming to terms with his identity during law school, Armstrong left Scouting, at a time when openly gay men were still banned.

He didn’t return until 2015, when the ban on gay leaders ended, and he’s now volunteering as a lodge adviser. This time around, he’s serving as an openly gay man, and hoping he can be the role model he never had as a gay youth.

“The ability to now watch youth be able to be who they are in Scouting [is] really touching,” he said. “This can be, maybe for some kids, the one place they're safe and comfortable in themselves.”

“The direction we're headed, for all youth to feel comfortable in the organization, is amazing,” Armstrong said. “Every every kid deserves a Scouting experience.”

A safe space for the next generation

Andy Martin came close to doing the same thing as Ross Armstrong: Leaving Scouting until the ban on gay leaders ended.

But the eagle scout and longtime OA volunteer stuck it out, and was surprised to see the 2015 policy change, which came out just in time to keep Martin involved.

As he’s continued to volunteer, Martin seems a lot of room for improvement to create a welcoming culture in Scouting, especially at the local level.

“Now, it's a matter of making sure that the next generation of scouts, that they have that safe space, and that they also know that they can talk to adults, and that we can potentially help them help them along their journey,” he said.

He knows not every adult volunteer is going to get their on their own, and wants to see more active outreach and resources given to scouters who are interested in being an affirming leader for the LGBTQ scouts in their charge.

“If we can train adult leaders to emulate or be the example that we want, I think that helps move the [needle], change the society.”