'Do you see any dichotomy between being gay and being a member of the Boy Scouts?'

A press conference outside the Supreme Court in 2000 illuminates the cultural moment when Dale v. Boy Scouts of America was roiling the nation.

It’s a sunny day outside the Supreme Court of the United States. A cluster of microphones sits idly in front of a bubbling fountain, its water a perfect robin egg blue.

A man in a suit strides confidently toward the mic stand, his introduction beginning before he even reaches the makeshift podium.

“Hi, I’m Rev. Robert Schenck, S-C-H-E-N-C-K,” he begins, clearly fluent in the format in which he’s about to speak, and attuned to the needs of television reporters.

Schenck is the general secretary of the National Clergy Council, whose member churches sponsor many a Boy Scout troop, Schenck is quick to note. And then he launches in: “This case is all about the government telling private organizations what they may believe and what they may practice.”

Schenck is the first in what becomes a lineup of religious representatives posted at the mic, warning of the dire implications of a case that has just been argued in front of the Supreme Court: Dale vs. Boy Scouts of America.

It’s April 26, 2000, and through the growing crowd of suited men, James Dale himself shuffles toward the mic stand, a smile breaking across his face as someone in the crowd cheers his name. Squarely in front of the cameras now, Dale takes a breath and turns to look at his attorney Evan Wolfson.

As Wolfson begins to speak, Dale’s parents maneuver in behind them, his mother smiling with apparent pride. A reporter begins asking a question, but Wolfson breaks in: “If I may just say, today is a very exciting day because we had the chance to tell the Supreme Court and tell the justices that New Jersey’s civil rights law is very important, it protects people against discrimination based on their sexual orientation, and that includes protecting gay young people, gay adults, as well as non-gay people, when it comes to participating in important organizations that we believe in like the Boy Scouts of America.”

Dale is here in front of the Supreme Court because a decade earlier he was removed from his role as an assistant scoutmaster in his New Jersey scout troop after council officials discovered that he was gay. What began as a local trial to regain his membership has become a national cause and a defining legal battle of the gay rights movement.

As Wolfson finishes his opening remarks, Dale stands beaming, a full head taller, ready to take the mic himself. Dale starts by thanking his parents and his lawyer, and then launches into talking points that surely feel familiar to him now: “I have always loved the Boy Scouts of America. It is a program that I hold dear to my heart. And I hope to one day be able to be back in the program.”

A reporter jumps in, asking: “Why did you bother to do this? Why did you bother to challenge this exclusion?” Dale and Wolfson eye each other, as if deciding who should take the question. “You’d already been through the scouts, you’d been an Eagle Scout. Why did you bother?” the reporter asks.

Dale opens his mouth, hesitates, looks and nods at Wolfson, then starts again: “I — I just believe in what Scouting is all about and I’ve always believed in Scouting. And the reason why I did this is because I care about the Scouting program,” he says, then immediately turns to Wolfson, who faces the press and asks, “Are there any other quick questions?”

There is one: “Do you see any dichotomy between being gay and being a member of the Boy Scouts?”

Wolfson takes this one. “As the record clearly shows, gay people are able to participate in Scouting. James won just about every award that Scouting had to offer,” he says. Mom smiles at this, and Wolfson continues. “He became an Eagle Scout, they chose him to be an assistant scoutmaster. There is absolutely no basis for excluding gay people who believe in this program from the ability to participate.”

Another reporter follows: “The scouts say you can’t be morally straight and be gay.” Not evidently a question, they ask the reporter to repeat it. “The scouts say you can’t be morally straight and be gay,” the reporter says again, then tilts the mic toward Dale, who is ready to respond.

“When I — when I first learned the definition of ‘morally straight,’ when I was 11 years old and in the Boy Scouts, it said to respect and defend the rights of all people,” Dale says. Wolfson nods emphatically. “To be honest and open in your relationships with other people. If anyone looks at the Scouting handbook today they’ll see the exact same phrase. Because that’s what being ‘morally straight’ is about. Standing up for yourself and being honest,” Dale says, his nerves now mostly gone, his response well-practiced and confident.

After a few more minutes of wonky legal questions, mostly handled by Wolfson, the whole group shuffles away from the mic.

The press conference flips back to the other side, with the next speaker lamenting the case’s potential to “destroy religious groups” and other organizations that “promote morality.”

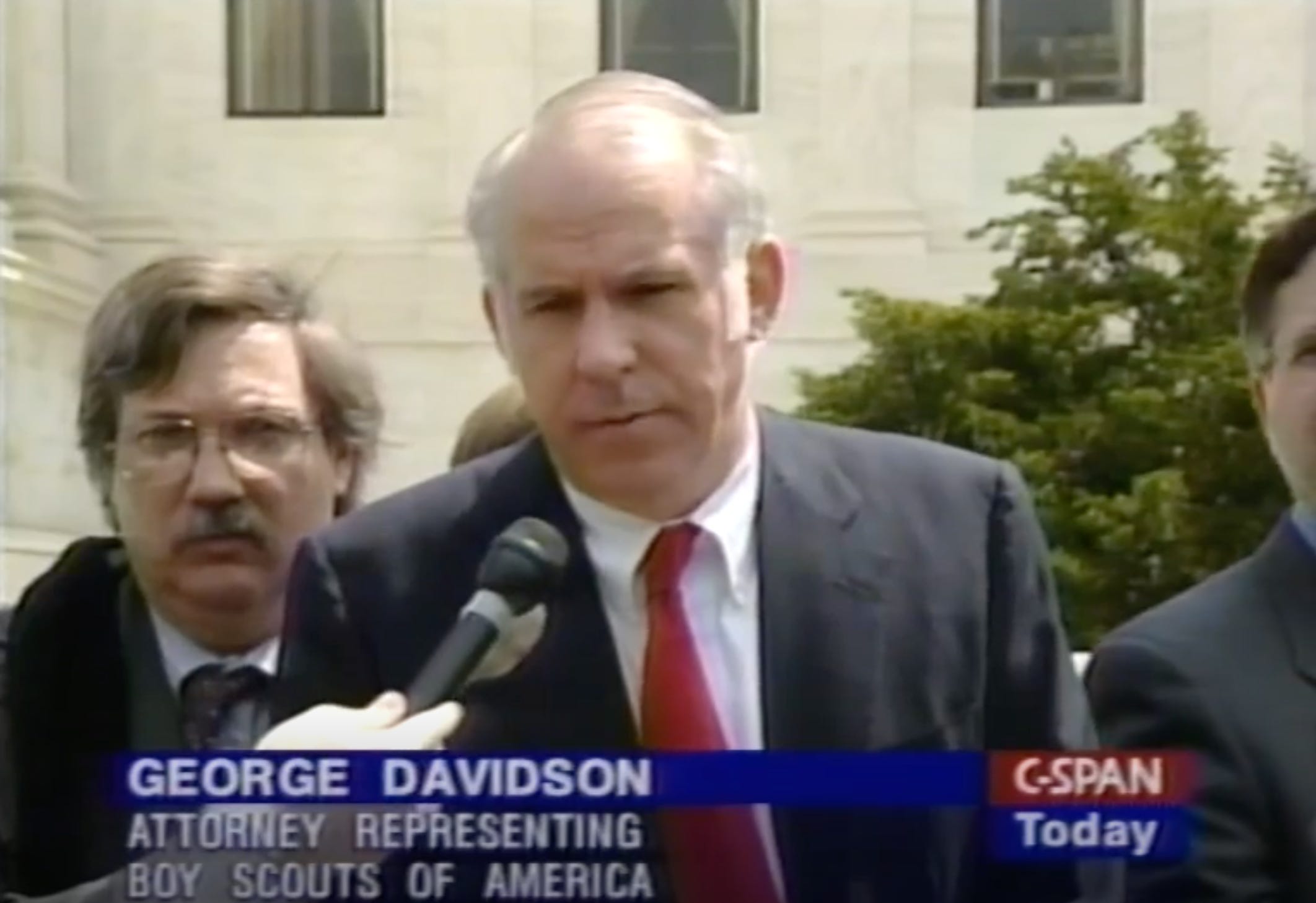

Eventually the BSA’s attorney, George Davidson, arrives at the mic. He tucks his glasses into his jacket pocket, eyes the reporters, then plainly states his name and title. He’s told repeatedly to look at the TV cameras, but looks down toward the ground as he delivers curt answers to the first few reporters, who don’t seemed satisfied.

“At its core, why should the Boy Scouts not permit an openly homosexual scout leader who has a long history as an ace scout?” one reporter prods.

Davidson responds, this time facing the reporter directly: “Well he had a long history as an ace scout before he became co-president of the Rutgers gay and lesbian club. And Boy Scouting takes the view, that comports with religions to which most Americans belong, that homosexual conduct is wrongful, and thus doesn’t appoint openly homosexual people as leaders.”

The reporter follows up: “Is not being a homosexual a core issue to being a scout?”

“The message of the Boy Scouts is what kind of behavior boys should engage in, and that’s morally straight and clean behavior,” Davidson says.

The questions eventually descend into specific hypotheticals about how the Boy Scouts’ anti-gay policy does or would apply, to which Davidson is not always sure, noting that most of the scenarios simply “haven’t come up.”

But Davidson hits his stride in his answer to the final question he receives that day: “It’s a fundamental issue of freedom of association. Society has room for the Boy Scouts and it has room for the gay men’s chorus. The government doesn’t have the power in the voluntary sector to remake every organization in accordance with the political fashion of the day. That’s for the private organizations to make their own decisions about.”

A beat of silence passes, and someone calls out, “Thanks very much.” Davidson nods, turns his back to the podium and walks away.

I’m sharing this flashback with you today — which you can watch in its entirety here on C-SPAN — because I think it says a lot about the cultural moment at the time of Dale’s Supreme Court case. The lineup of speakers and the questions repeated by reporters illustrates a lot of the attitudes surrounding the case, in which the Boy Scouts prevailed but which ultimately failed to settle the gay membership debate.

What’s your takeaway from this press conference? What surprised you? What did you notice?