In memory of David Knapp

The legendary Scouter-turned-activist passed away at the age of 97 last weekend.

In the fall of 2021, I made one of my first trips into the post-vaccine world that was just starting to open up again.

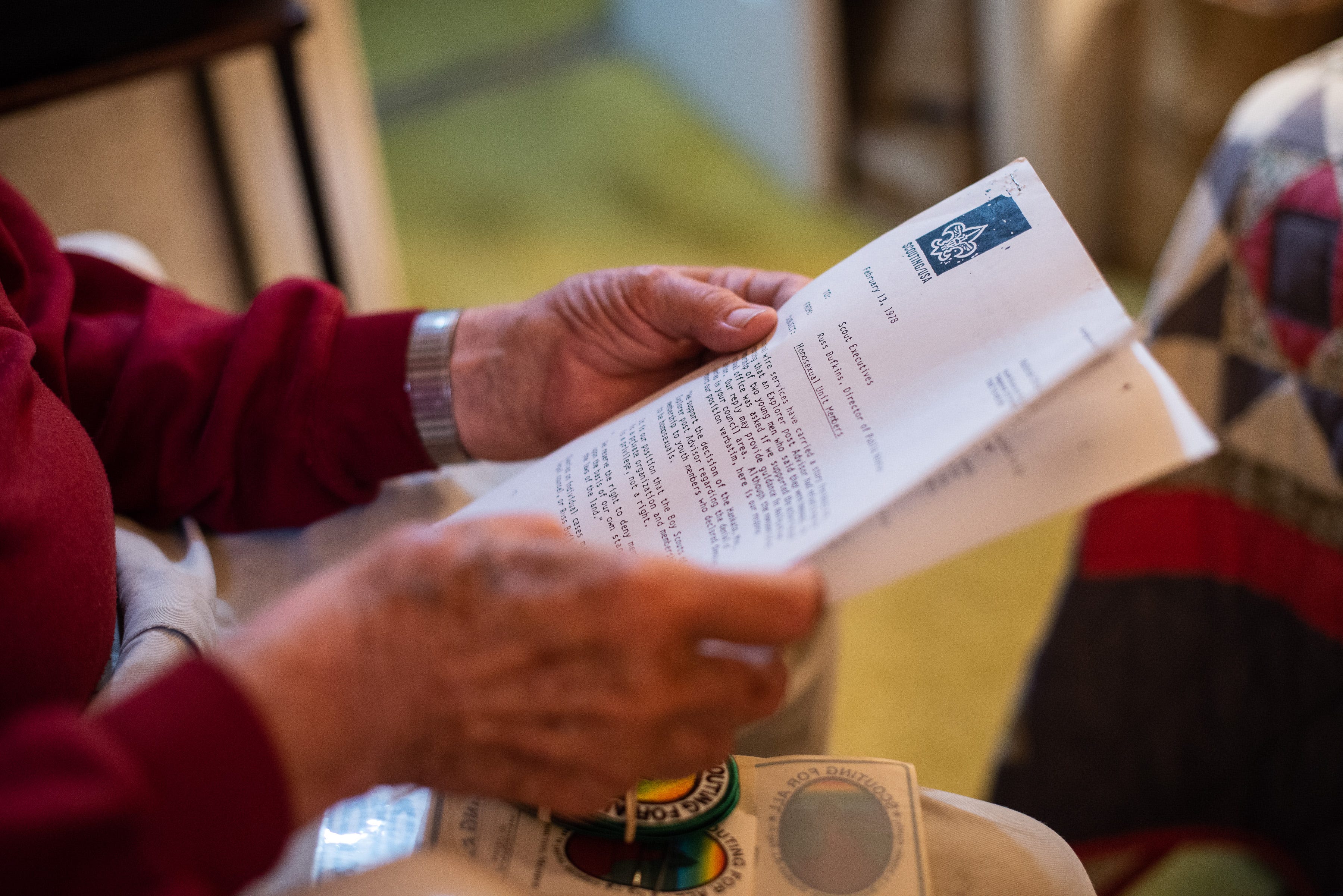

I traveled to the small town of Guilford, Connecticut, to meet someone I had spent hours on the phone with during quarantine: David Knapp. Many of you know Knapp as a legendary gay scouter who fought for more than 20 years for acceptance in the organization he loved.

Knapp was 94 years old in 2020, when we first began talking. It started as an interview for a series of Pride Profiles I was working on, and then grew into something of a friendship. Knapp would call unannounced, and start telling some fascinating story, then stop to make sure he wasn’t taking up too much of my time, and at my urging he’d weave that story into another. In those times of dire uncertainty, there was something extremely comforting about our conversations, like talking to a grandparent.

I was also aware that, at Knapp’s age, every moment I had with him was a gift. So when it was safe enough, I planned a trip to Connecticut, with the goal of reporting a magazine-length feature about his absolutely incredible life.

The two days I spent with him left me overwhelmed with stories, notes and photos. When I got home, I immediately got to work pitching a profile of Knapp to every national publication and magazine I could think of. But as days turned into weeks and months, the rejections piled up. No one seemed to want Knapp’s story (or at least, my version of it), and I eventually let it fall off my radar, too.

Until this week, when I learned that Knapp passed away at the age of 97. I regret never being able to publish his story, but I feel the need to honor his life in some way, so I’m going to do so here. I hope you’ll indulge me. Here is the story of David Knapp.

David Knapp, born in 1926, was a child of the Great Depression. He grew up in a farming village of about 50 homes, on the outskirts of Highland Park, New Jersey. He described his neighbors as a mix of Hungarian, Polish and Italian immigrants who kept cows, chickens and pigs on their property. “It was definitely blue collar,” he told me.

But his family occupied a distinctly different social class. Knapp’s father, though originally a high-school dropout, ended up attending Harvard and becoming a vice president at Johnson & Johnson. He also built a summer cabin for his family, on one of northern New Jersey’s many mountain lakes, where Knapp would discover his love for the outdoors—learning to canoe and eventually sail.

Knapp’s introduction to Scouting came at an early age, when his dad signed him up for a troop at a church in New Brunswick. He didn’t know a single boy there at first, but came to love the program. “It was good bunch of guys, and we had a wonderful scoutmaster,” he said.

He especially enjoyed summer camp, which at the time cost each scout $8 to attend for the week. Describing the camp to me, Knapp reveled in the gritty details: 80 kids sharing a scant few latrines, and “no showers, no nothing.” He was focused, instead, on the merit badges, quickly shooting up to first class rank. Scouting was one of the only activities he enjoyed during his middle school years, when he attended an academically rigorous school that lacked any kind of extra-curriculars (“No gym, no music, no clubs, nothing. Nothing!”)

High school was a welcome change. Knapp’s mother paid to send him to a suburban high school with a better reputation than the city school he would have otherwise attended. “I was like a kid in a candy shop. Because I'd had nothing: no gym, no music, no clubs, no nothing. No sports,” he said. “And so I tried everything. Everything.”

Knapp joined sports teams (“I was terrible”) and the band (“I couldn't even play”), undeterred by his lack of ability in either. His classmates elected him homeroom president. He was so busy, even his freshman year, he easily could have let the Boy Scouts drop by the wayside—especially because his troop had become rowdy and unproductive under the leadership of a new scoutmaster, leaving Knapp frustrated. He was ready to drop out.

But a friend from a different scout troop stepped in with a last-ditch effort to keep Knapp involved. He brought Knapp to a meeting and convinced him to transfer in. The new troop, with a stronger focus on rank advancement, was enough to keep Knapp interested and on the path to eagle scout. “That little incident and decision that I made at the age of 14 was the life-changing decision. That influenced my whole life,” he said.

The summer after Knapp’s junior year, the local scout executive called and asked him to serve as the waterfront director at the same camp he had attended growing up. Knapp jumped at the opportunity, even though it didn’t pay. “I was very good at canoeing and rowing and swimming,” he said.

All this time—through middle and high school, through Scouting—Knapp never considered he might be gay. “Never entered my head. Never occurred to me,” he said. “I had girlfriends, but certainly was never even thought of sex. Just didn't exist.”

Knapp went on to study at Wesleyan University, and then Rutgers, with the goal of becoming a high school teacher. But his early teaching experiences left him burn out and discouraged, so he pivoted and took a job as a professional Scouter.

The career turn left his parents, and their peers, somewhat embarrassed; they deemed his job with the Boy Scouts “a waste of his Wesleyan education.” Knapp explained the career expectations in this post-war period: “No one went into social work. That was the lowest of all things.”

It seemed the BSA was equally skeptical of Knapp’s career choice: “The personnel director who hired me … didn't think that I was enough of an outdoor ‘he-man.’ And that infuriated me because I was as much of an outdoor man as anybody could be. I loved the outdoors, and did a lot of it, and had the proof that I did do it,” he said. “I had a feeling that he was prejudiced against Ivy League.”

Once Knapp settled into his role as a district executive, any doubts about his abilities quickly vanished. He helped charter new units all over his territory in Long Island. “I was like an itinerant preacher, going from village to village,” he said. He worked 40 hours a week in the office, plus countless nights and weekends at Scouting events. Knapp’s district often ranked number one in the council for membership.

He loved the work, but once he married and started a family, he could no longer keep up the crazy hours. So he started a new career as a textbook salesman. The company’s annual meetings sometimes took him to Miami, where on one trip he had something of a gay awakening after wandering into the “homosexual section” of a movie theater one night. “What I saw totally enthralled me and fascinated me and hooked me. I was already hooked anyway, I guess. But that was a clear indication that this is where I was at,” Knapp said.

Years later, during the 1980s, he was working for a company that sold phonics workbooks, and would travel across New England on business, often to Boston. He stumbled upon a gay bookstore there, which had a directory of gay bars in the city. He started checking them out in the evenings after work meetings. He marveled at the cliques of 20- and 30-year-old gay men, who incidentally showed no interested in the 50-year-old Knapp (“I didn't expect them to”). Some afternoons, he’d sneak off to gay bathhouses, which “absolutely were just heaven” in his eyes.

But these experiences also “created tremendous internal conflicts,” Knapp said, “because I was violating my marriage vows.” Back home, he was also a well-known community member, running for president of the board of education, among other things. “If the word had ever gotten out [that I was] going to gay bathhouses, it would be catastrophic.” Top it all off, AIDS was beginning to spread like wildfire, decimating the gay community. “It's a miracle that I didn't get AIDS,” Knapp said.

He eventually met with a gay men’s group at Yale, and an affirming local Episcopal priest, both of whom helped him realized he needed to start being honest with the people around him. “I still wasn't out to my wife,” he said. “So for 10 years, from age 50 to 60, I was in the closet, and also having gay sex. It was a period of absolute hell, really absolute hell.”

When Knapp did finally come out to his wife, she took it well, all things considered. The two separated, allowing each other to lead more honest lives, but they remained friends. She even helped Knapp find a new home (where he lived until his death) and furnish it. She remarried a few laters later.

Knapp’s own daughter wasn’t so supportive. He told me that “she doesn't approve of my being homosexual. [She thinks] that I can be saved, that I don't pray hard enough.” The cold relationship trickled down to his grandsons, who didn’t seek a close a relationship with their grandfather.

These weren’t the only issues that Knapp faced in his family after coming out.

One afternoon, when Knapp was at home in his living room, he heard a knock on the door. Behind it was the vice president of the local Boy Scout council, where he had started volunteering again some years earlier. The man told Knapp: “We have bad news for you. You're being expelled from the Boy Scouts of America.”

Knapp sat there in total shock. He asked, what had he done wrong?

“You haven't done anything,” the council official responded.

“Well, then why are you expelling me?” Knapp replied.

“Do you really want to know?”

“Of course I want to know.”

“We have discovered that you are a homosexual.”

Still shocked, Knapp started to wonder how they found out. They told him that they had received a letter from South Carolina telling them he was gay. “And there was only one single person that could possibly have done that,” Knapp recalls. It was his stepdaughter, who had never accepted him for being gay.

“I called her on the phone. And she admitted that she wrote the letter,” Knapp said. “She knew how much the Scouts meant to me. I [couldn’t] believe it then, I still can't believe it now.”

His anger was compounded by the fact that the BSA didn’t even have an anti-gay policy until 1978, three decades after Knapp had earned his eagle scout rank and been trained as a professional Scouter. Like so many others, Knapp had dedicated much of his life to Scouting without ever knowing his very identity made him ineligible for membership.

The expulsion galvanized him: “I said, I’m going to fight the Scouts on this issue until the day I die.”

Knapp did just that.

He picketed local councils. He organized a PFLAG chapter in his church. He wrote letters to the editor. He marched in the New York City pride parade in a Scout uniform year after year. He protested at BSA national meetings in Miami, San Francisco, Boston and Philadelphia.

But nothing seemed to change. When I asked him if he ever felt like giving up, he was incredulous. “You mean giving up the battle? Oh, it never entered my head. It never entered my head.” He didn’t expect to ever win, but he would fight anyway.

20 years passed, until the Boy Scouts gay membership issue was thrust back into the spotlight in 2012 by a number of activists and the newly-formed group Scouts for Equality.

A year later, David Knapp found himself holed up in a hotel room with a bunch of volunteers from Scouts for Equality, not far from the BSA headquarters in Dallas. At the Scouts’ national meeting, representatives from around the country had just heard arguments on both sides of Scouting’s most controversial issue: Whether to allow gay youth.

Four hours after the speeches were given and votes were tallied, the phone rang in Knapp’s hotel room. The result was in: 62% in favor of gay scouts. The policy passed. The whole group jumped up, yelling and screaming. Knapp and the others burst into tears.

“That’s a moment I will never forget in my life,” he said.

Did you know David Knapp? Please share your memories of him in the comments.

A memorial service for David will be held Monday, August 14th at 10 a.m., at the First Congregational Church at 122 Broad St. in Guilford. The American Cancer Society and American Heart Association are accepting donations in his honor.